The early beginnings of NLR

The emergence of (military) aviation

After military aviation had clearly proved its worth during the First World War, in late 1917 the Dutch Government decided to substantially expand its air arm in the interest of the nation’s defence. The major importance of developing a national aircraft industry was the uncertainties involved in being able to source materials from abroad in times of war, as all countries had found out first hand.

As the Netherlands went on to focus on developing aircraft types of their own design, this soon laid bare the lack of technical-scientific assistance available to the aircraft industry. In addition, the aircraft users and the Ministries of War and the Navy were in need of this kind of assistance to help them define the specifications which their aircraft had to comply with.

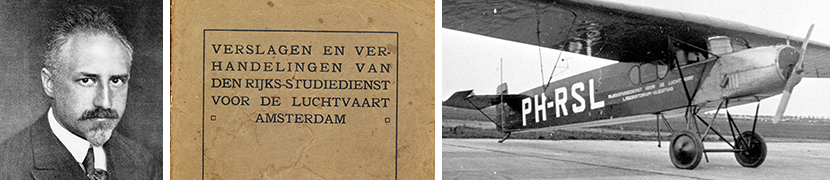

By putting in place relevant regulations, the Government wanted to drive down the number of accidents. This situation prompted to put a proposal to set up the Aviation Engineering Research Department (Rijks-Studiedienst voor de Luchtvaart – RSL). Rd. Eng. E.B. Wolff was appointed as the Director of this new department.

Establishment of Rijks-Studiedienst voor de Luchtvaart – RSL (Aviation Engineering Research Department)

The RSL was officially inaugurated on 5 April 1919, at the Naval Dockyard in Amsterdam North. The RSLs remit was to conduct technical-scientific research into aviation issues, which the aircraft builders or users were unable to solve by themselves because of the lack of the appropriate equipment and specialist know-how and experience.

The problems faced back in the day primarily revolved around the kind of forces that impact on an aircraft moving through the air. To perform aerodynamic tests, a wind tunnel was built which continued to be used until 1940. The development of a national aircraft industry received a powerful boost by the return to The Netherlands of Fokker and Koolhoven, who went on to focus on building commercial aircraft.

For civil aviation, even more so than for military aviation in war time, the element of safety was paramount. In this context the focus went out to devising solutions to technical issues, in which especially the economic aspects were of the essence. Moreover, the development of civil aviation also demanded state supervision of the airworthiness of aeroplanes.

After the war ended, in 1919 the military significance of aviation faded into the background. This was offset by the rising interest in the opportunities aviation presented for the airborne carriage of passengers, which led to the incorporation of the KLM that same year.

More focus on scientific research work

These developments conspired to see the RSL – which up until then had been operating under the Ammunitions Bureau – assigned to the Ministry for Public Works and Water Management in 1920. From this time forward, the RSL was tasked with the supervision of the construction and repairs of aircraft and engines, and with preparing, and as necessary, amending technical standards to obtain certificates of airworthiness of aircraft, gliders and engines. The RSL was also tasked with the verification of strength calculations of materials, flight characteristics and of aircraft’s airworthiness. For aircraft imported from abroad too, the RSL checked to see if they complied with the applicable requirements.

It was not until after the RSL had put forward a positive opinion that airworthiness certificates were awarded by the Ministry for Public Works and Water Management, that is to say by the Ministry’s Aviation Bureau which was transformed into the Aviation Department in 1930.

The RSL, which performed research for the aircraft industry as well as handling the inspections of aviation equipment, would need to be relieved from its inspection duties, to free up time for scientific research. The above considerations led the Government to transfer the inspection of aviation equipment to the Aviation Department and to transform the RSL into a foundation. On 14 June 1937, the Minister for Public Works and Water Management enacted the Decree establishing the foundation, which was assigned to manage the RSL’s equipment. In addition, the Scientific Committee was established, made up of experts in the various disciplines involved in aviation. The Committee’s remit included assessing the proceedings and activities of the NLL, with particular attention going out to the scientific foundations thereof and delivering opinions regarding the work plan to the Board.

The quarters at the Naval Dockyard – in which the RSL had been billeted when it was launched and which were only ever intended to be provisional – had proved to be inadequate for quite some time. Moreover, the RSL was in urgent need of a new wind tunnel with larger dimensions that delivered higher speeds. In 1938, the board decided to have a new building constructed, with two new wind tunnels at Sloterweg, the connecting road linking Amsterdam and Schiphol. This building, which was occupied immediately after the outbreak of the Second World War even though it was unfinished at this stage, was completed in 1941.

Reconstruction aircraft industry and extension of the Nationaal Luchtvaartlaboratorium (NLL) (National Aviation Laboratory)

The Government’s decision in 1946 to provide support to rebuild the Dutch aircraft industry and the associated establishment of the Dutch Aircraft Development Institute – Nederlands Instituut voor Vliegtuigontwikkeling (NIV) prompted the laboratory to prepare for a new task: performing the kind of activities that were needed without further ado to get the industry off the ground again. This was one of the reasons that impelled the expansion and modernisation of the laboratory.

The development of new measurement and test methods and the associated equipment soon allowed for the laboratory’s rising needs to be met for assistance with the development and testing of the prototypes of the Dutch aircraft industry and with solving issues seen in the aircraft that were being used.

A major turning point in the research activities was the arrival in 1955 of the computer, a greatly welcome tool to help solve the often highly complex mathematical problems encountered. Due to the expansion of the research facilities and the lack of space at the Amsterdam site, in 1957 a second site was commissioned in the Noordoostpolder.

Space industry on the rise

The launch of the first (Russian) satellite in 1957 marked the start of the space age and the associated space technology in which the laboratory also became involved, prompting a name change in 1961. From 1960 forward, The Netherlands took part in European space programmes. A year later, the NLL was renamed as National Aviation and Aerospace Laboratory – NLR.

For the first European rockets, NLR was in charge of the guidance system, the aerodynamics and wind tunnel measurements. With aerospace in its portfolio, NLR grew in strength. The first major Dutch contribution to the global space age effort was the launch of the first Dutch astronomical satellite in 1974. Followed in 1983 by IRAS, the world’s first infrared astronomical satellite. NLR assisted in the development of both satellites. This accumulated knowledge forms the basis for new technologies in the field of satellites, such as clusters of small satellites.

Developments at the end of the 20th century

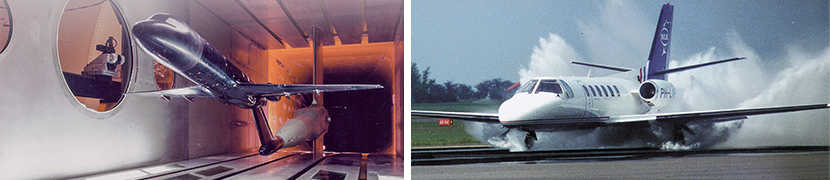

Over the last 3 decades of the 20th century, NLR mainly focused on supporting Fokker with the research and development and the testing of the Fokker 50, Fokker 100 and Fokker 70 aircraft. NLR was given modern research facilities, such as a large subsonic wind tunnel and simulators to test aircraft and flight procedures in specific situations and for air traffic purposes.

Powerful computers became available that enabled NLR’s engineers to resolve complex mathematical problems much quicker. A new jet-powered laboratory aeroplane was purchased in association with the Delft University of Technology. Over this time period, NLR became an increasingly more international player in all manner of partnerships. In yet another international alliance, NLR and its German sister organisation DLR joined forces in the German-Dutch Wind Tunnels organisation.

To NLR, Fokker’s bankruptcy in 1996 brought a substantial reduction in the scope of its activities in the areas of aircraft development and flight testing. To a large degree, this was offset by the added work in the area of aircraft usage. After Fokker and subsequently the NIVR ceased to exist, NLR tapped into new international markets.

NLR-Netherlands Aerospace Centre

In 2016, NLR’s name was changed into the Netherlands Aerospace Centre, maintaining NLR abbreviation. A name that is better geared to the role NLR is seeking to play in times to come. Technology developments are coming thick and fast, with the complexity of systems rapidly rising. At the same time, society is holding out increasingly greater demands in terms of security, sustainability and transparency, in particular in NLR’s fields of discipline.

NLR is expected to deliver know-how for integrated solutions. NLR is still the independent knowledge organisation that serves a wide range of national as well as international customer groups: industry as well as operators; defence as well as civil aviation and aerospace, in the Netherlands as well as abroad. Strategic partnerships with both the world of trade and industry, universities, other Dutch technology institutions and international research organisations are crucial in this respect.

Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre

The crowning glory at NLR’s work followed the 100th anniversary of NLR on 5 April 2019 when NLR received the Royal predicate on behalf of His Majesty King Willem-Alexander. The award stands for the quality and recognition of NLR as a leading technological knowledge institute in the field of aerospace in the Netherlands. NLR can now call itself Royal NLR.

This overview has been created with valuable contributions of former employees and pensioners of NLR and Stichting Behoud Erfgoed NLR.

We have done our best to find all rights holders with regard to (photo) material on this website / newsletter. We ask anyone who believes that his / her material has been used here without prior permission to contact us.