Nevertheless, it stirred up emotions. Corendon said it had little sympathy for it and instead advocated the banning of so-called ultra-short flights of up to 500 kilometres, and was then portrayed on LinkedIn as an ‘entrepreneur who wants to antagonise its competitors through legislation’. Fellow aviation expert Joris Melkert expressed a more positive view of the plans (‘fairer variant’) on Luchtvaartnieuws (paywall), but this was also met with criticism online. Time for a factual analysis.

How much do different flights contribute to CO2 emissions?

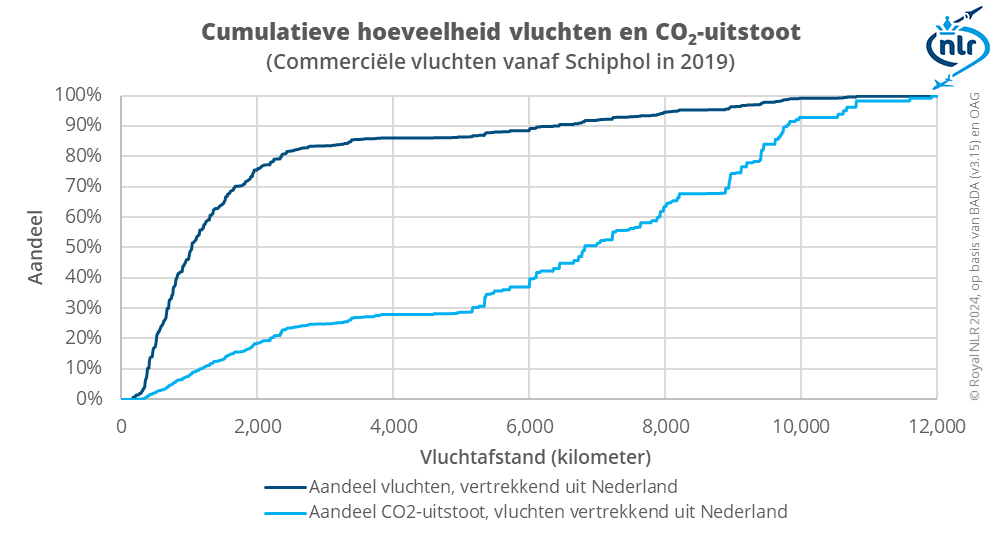

To answer this question, we at NLR calculated CO2 emissions for all flights departing from Schiphol. We did this for the year 2019, since the following years paint a distorted picture because of the impact of COVID-19. We then sorted the analysed flights from short to long haul. Finally, we added up the number of flights for the different distances with the corresponding CO2 emissions to get cumulative amounts. This resulted in the following graph.

The chart shows that around 75% of flights take place on routes of up to 2,000 kilometres (from the Netherlands to, say, southern Portugal or Iceland). Together, these flights are responsible for almost 20% of CO2 emissions. This also means that the 25% longest flights (beyond 2,000 kilometres) are responsible for over 80% CO2 emissions. The longer the distance, the more skewed the distribution: about 10% of flights are longer than 6000 kilometres (such as to New York or Delhi) and these contribute over 60% of CO2 emissions. Or, conversely, more than 35% of CO2 emissions are caused by just 5% of flights – those longer than 8000 kilometres (Seattle or Beijing).

Long-haul flights are smaller in numbers, but they are responsible for the majority of CO2 emissions. Raising the air passenger tax on those longer flights will make those tickets more expensive, and even fewer people are likely to fly that far. Thereby, it is likely to contribute to reducing CO2 emissions from aviation.

But I thought it was the shorter flights that were the problem?

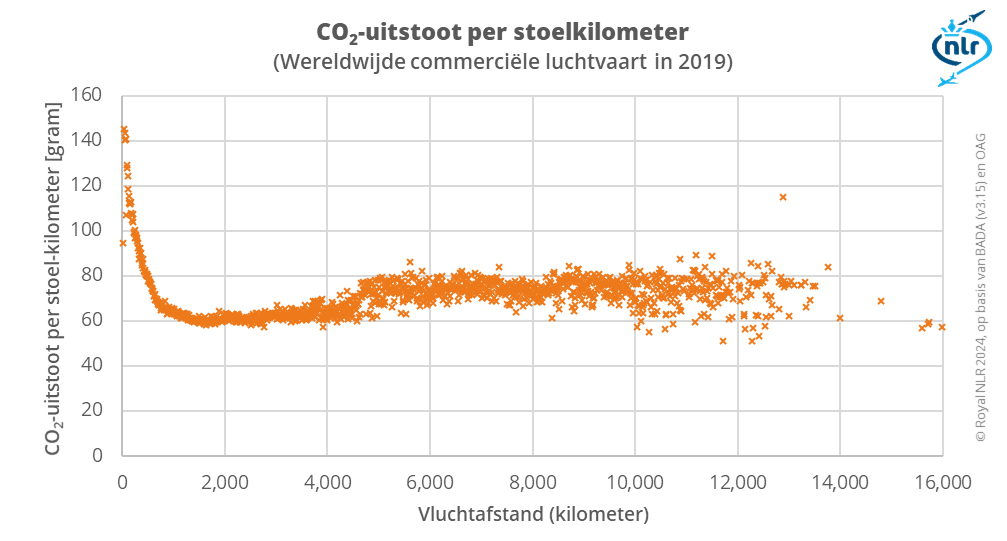

That is understandable, since many interest groups focus on reducing short flights. And in the end, it all depends how you look at things. As shown in the graph above, long-haul flights result in more CO2. If we consider CO2 emissions per seat (the so-called seat-kilometre), as shown below, is a different story, however.

This shows that it is exactly the (ultra) short flights that haver a higher load: these flights emit more CO2 per seat-kilometre than the longer flights. The shorter the flight, the greater its proportion in terms of take-off and climb, during which fuel consumption is higher. On longer flights, it is exactly the opposite: there, a larger part is namely the cruise flight, where the aircraft is most fuel efficient at high altitude. For very long flights, the CO2 emissions per seat kilometre do increase again, since the aircraft then has to carry more fuel, and fuel consumption increases with aircraft weight.

By the way: the above applies only to CO2 emissions. There are obviously other aspect to consider as well. Noise, for instance, also constitutes an important environmental impact of aviation. However, this varies much less with distance and much more with the size of the aircraft. The focus on short flights can also be explained by the fact that there are more alternatives, such as trains. And of course, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, trains are much cleaner.

What about the countries around us?

A 2020 survey by the national government shows that several countries already have distance-based air passenger taxes. Some additionally differentiate by seat class (economy class or business class). Germany has had a tax distinguishing between short, medium and long-haul flights since 2012 – the UK since 1994. A bit further, Austria, France, Italy and Sweden also have higher air passenger taxes for longer flights than for shorter flights.

Conclusion?

Increasing the air passenger tax for longer flights is likely to contribute to reducing CO2 emissions. The reason for that is that it increases the ticket price for long-haul flights, which – as evidenced by many studies – means fewer people will take such flights. This, in turn, reduces emissions. Moreover, another study shows that the prices of precisely long-haul flights are relatively low compared to the cost of the climate impact those flights have. So from a climate perspective, this intention seems like a good idea. However, as is often the case, several factors – noise, but also network quality and airlines’ revenue model – come into play when making a balanced choice. The last word has certainly not been said in this matter.