Zonder windtunnelmodellen, kan er geen vliegtuig de lucht in

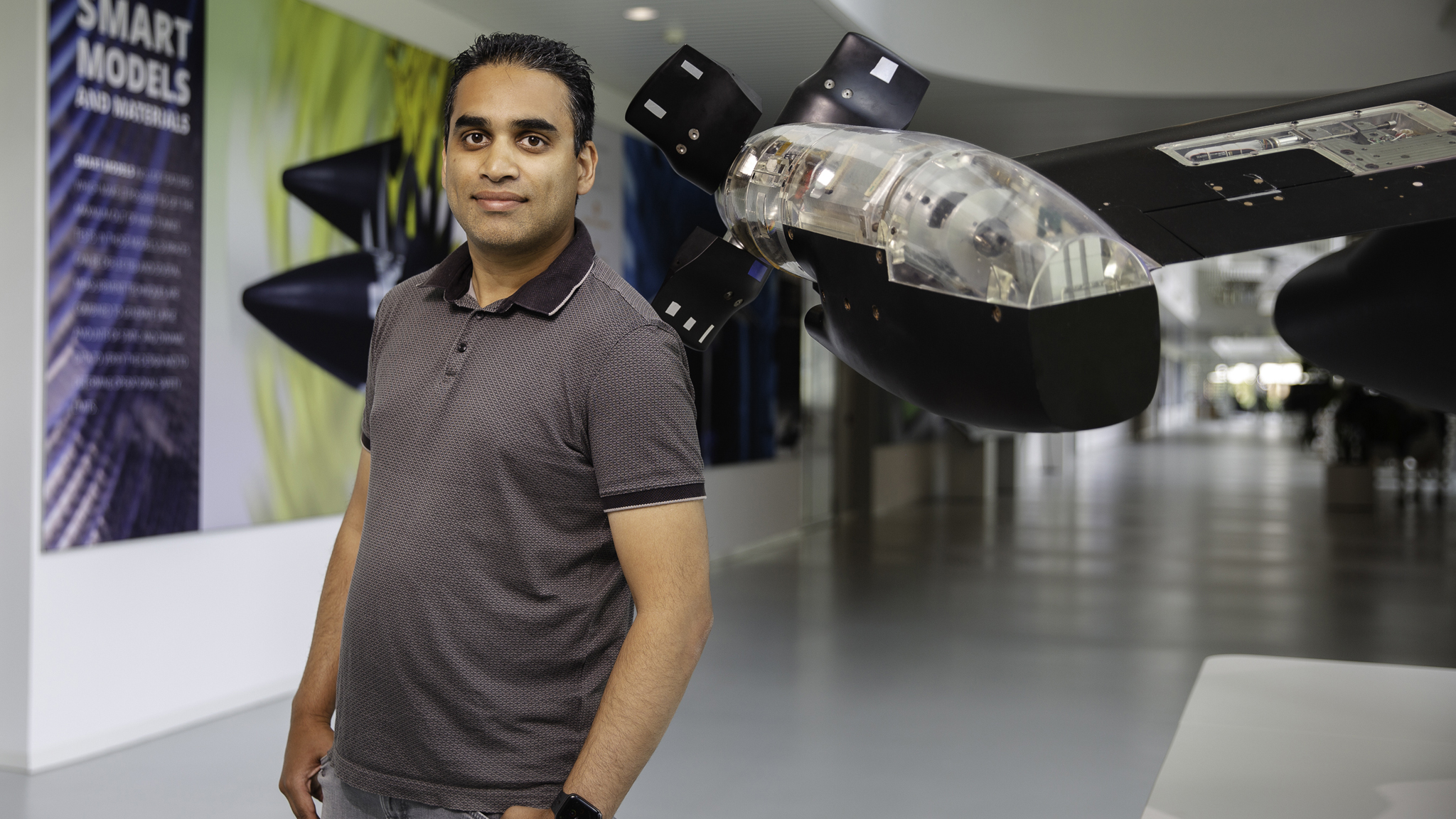

“Voor de Ariane 6 (het nieuwste raketmodel van ESA, red.) die in juli 2024 succesvol gelanceerd werd, hebben wij in 2014 al de eerste windtunnelmodellen gemaakt. Dat alles rondom de lancering goed verliep, gaf een enorm gevoel van trots.” Als Mechanical Design Engineer bij het Koninklijk Nederlands Lucht- en Ruimtevaartcentrum (NLR) werkt Shafeeq Kasiemkhan met vliegtuigen, helikopters en raketten die de rest van de wereld pas ziet als ze jaren later de lucht ingaan.

Het testen en valideren van nieuwe toestellen met windtunnelmodellen is onmisbaar voor het de luchtvaart van morgen. De modellen worden gebruikt voor de ontwikkeling van nieuwe vliegtuigtypes en onderzoek naar innovatieve technologie. Het geeft vliegtuigbouwers de kans om – voordat er überhaupt een prototype gebouwd is – optimale aerodynamische eigenschappen te bepalen. Daarnaast besparen de simulaties zowel kosten als tijd en vergroot het de veiligheid; problemen kunnen geïdentificeerd en opgelost worden voordat het nieuwe toestel de lucht in gaat.

NLR beschikt in Marknesse over een state-of-the-art faciliteit met een eigen workshop waar de modellen op één plek worden ontworpen, gebouwd en worden voorzien van geavanceerde meetapparatuur. Ook deze geavanceerde apparatuur – zoals balansen, waarmee de belasting op een model in alle richtingen met hoge precisie kan worden gemeten – worden door Shafeeq en zijn team ontworpen.

Dat deze one-stop-shop van NLR en de windtunnels van DNW (German-Dutch Windtunnels) zich in Marknesse op nog geen vijftig meter van elkaar bevinden, maakt het een unieke testlocatie. NLR ontwerpt windtunnelmodellen voor internationale onderzoeksprojecten en vliegtuigfabrikanten in Europa, Brazilië, Zuid-Korea en de Verenigde Staten.

Heel snel, heel veel data verzamelen

“Zie je die grote tunnel daar?”, vraagt Shafeeq terwijl hij vanuit zijn kantoor op de campus van NLR in Marknesse naar een grijze installatie van 9,5 bij 9,5 meter wijst. “Dat is de Large-Low speed Facility (LFF), een windtunnel met een gesloten retourcircuit. Hier kunnen we testen met snelheden tot 550 kilometer per uur.” De tunnel is voornamelijk geschikt voor aerodynamisch en aero-akoestisch onderzoek tijdens start- en landingsfases en groot genoeg om volledige vliegtuigconfiguraties te testen.

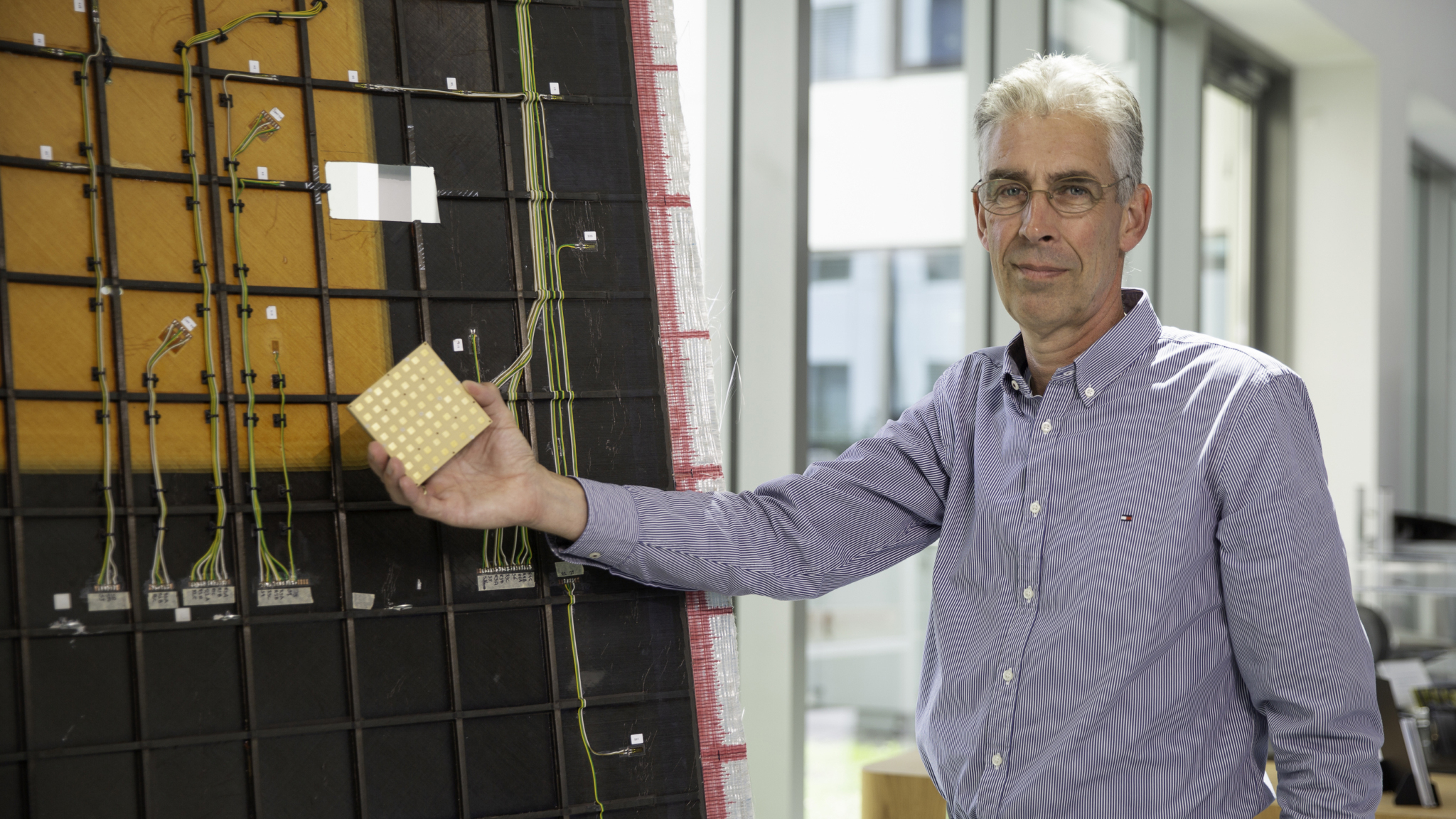

Shafeeq: “Op de windtunnelmodellen zitten duizenden sensoren die onder andere de drukverdeling, luchtstroomprofielen, geluidsproductie, en temperaturen op het modeloppervlak kunnen meten. Er kan met een windtunneltest dus snel heel veel data verzameld worden.”

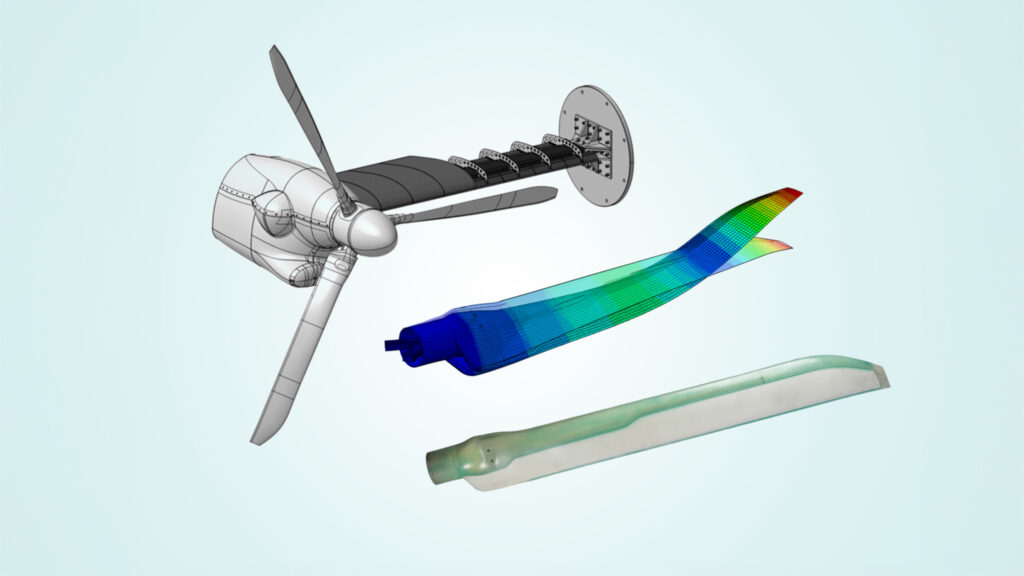

Zo werkt hij aan windtunnelmodellen met nieuwe materialen (denk aan: het vervangen van staal voor carbon of glass fibre) en vleugelstructuren. In de toekomst zullen vliegtuigen nog lichter en flexibeler worden, wat betekent dat flutter een groter probleem wordt. Om dit te kunnen analyseren, ontwikkelde zijn team een nieuw windtunnel vleugelmodel die het mogelijk maakt om trillingen in real-time te analyseren tijdens windtunneltests.

“Ik houd ervan om de grenzen op te zoeken en buiten de gebaande paden te gaan. Om als het technisch moeilijk wordt, alsnog een oplossing te verzinnen”

De grenzen opzoeken

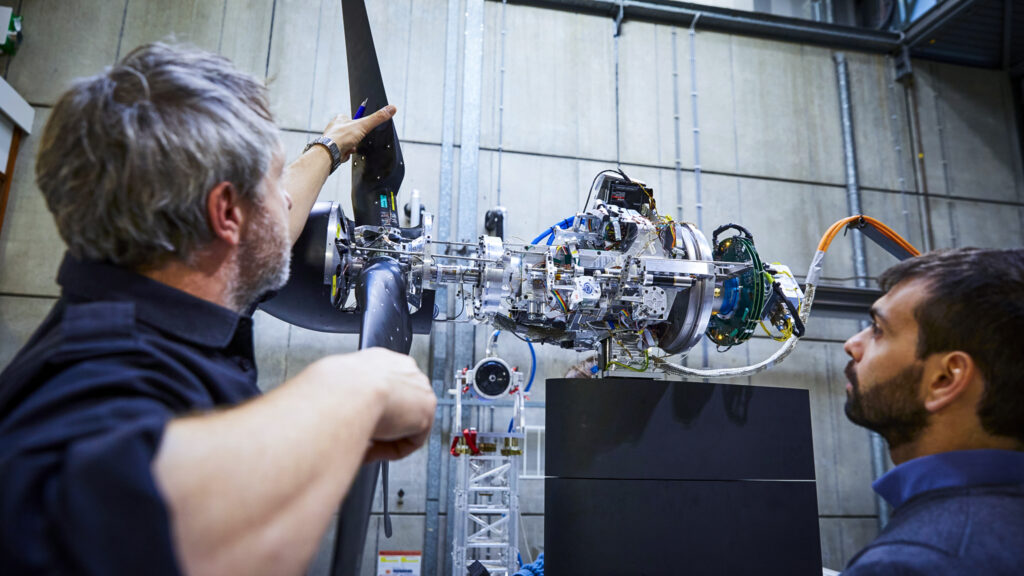

Een ander onderzoek waar Shafeeq nauw bij betrokken is, is het ATTILA-project: een Europees platform voor windtunneltesten van tiltrotors. Een van de milieu- en mobiliteitsdoelen van de EU is dat burgers in 90% van de gevallen in 4 uur van deur tot deur kunnen reizen. Om dat doel te halen, is er een nieuw soort toestel nodig dat tussen conventionele helikopters en vliegtuigen in zit. Daar komen tiltrotoren om de hoek kijken. De rotoren van een tiltrotor kunnen kantelen (tilten), waardoor het toestel horizontaal kan vliegen op hoge snelheid én verticaal kan opstijgen en landen – wat enorm veel ruimte bespaart.

Bij tiltrotors is het mechanische samenspel tussen de vleugel en de rotor moeilijk te voorspellen. Dat brengt in het bijzonder een grote uitdaging met zich mee, legt Shafeeq uit. “Aan de vleugel van een tiltrotor zitten drie bladen. Whirl flutter treedt op wanneer de bewegingen van de rotors en de vleugels van een vliegtuig elkaar beïnvloeden en versterken. Je wilt ze dus collectief, maar ook onafhankelijk van elkaar kunnen instellen en in trilling brengen om de situatie in een windtunnel te kunnen nabootsen”, legt Shafeeq uit. Bij DLR ontwierpen ze een apparaat dat dit kan, maar dat bleek te lomp en te zwaar en klopten aan bij NLR.

Shafeeq speelde een sleutelrol in de ontwikkeling van een mechanisch (en dus veel lichter) apparaat. Het model is inmiddels succesvol getest en er is een octrooiaanvraag gedaan voor het ontwerp. Antwoorden vinden op haast bijna onmogelijke, vragen, is wat hij het leukste vindt aan zijn werk. “Ik houd ervan om de grenzen op te zoeken en buiten de gebaande paden te gaan. Om als het technisch moeilijk wordt, alsnog een oplossing te verzinnen, zoals in het geval van ATILLA. Als ik iets moest noemen waarop ik trots ben in mijn carrière, dan is dat het wel.”

De nieuwe generatie constructeurs

Of hij nou naar Schiphol ging om vliegtuigen te spotten, spreekbeurten hield over de ruimte, of raketten nabouwde: Shafeeq was als jongetje altijd bezig met lucht- en ruimtevaart. Hij begon aan een mbo-opleiding vliegtuigonderhoudstechniek, liep stage op Schiphol en besloot nog een hbo studie vliegtuigbouwkunde te doen. Inmiddels loopt hij al tien jaar rond in de gangen van NLR.

Het belangrijkste advies dat hij zelf ooit kreeg – ‘Je moet altijd streven naar perfectie – komt van een collega die inmiddels met pensioen is. “Ik heb een first-time-right beroep: een windtunnelmodel ontwerpen, maken en testen is heel kostbaar, dus het moet in een keer goed werken. Daar heb ik in het begin aan moeten wennen, want dat brengt een bepaalde druk met zich mee.”

Het is – onder andere door deze druk – best een uitdaging om goed personeel te vinden. Daarom vindt Shafeeq het belangrijk om tijd, moeite en aandacht in de begeleiding van stagairs en nieuwe medewerkers te stoppen. Iets wat hij volgens zijn collega’s als geen ander kan. Hoe hij dat precies doet? Zijn pupillen moeten vooral gewoon doén, in het diepe springen.

“Ze moeten de kans krijgen om fouten te maken, daar leer je het meeste van. Ik vind het gewoon heel belangrijk dat de volgende generatie constructeurs goed begeleid wordt. Zij zijn de toekomst van onze afdeling. Op onze afdeling ontwerpen we de hardware en beneden in de werkplaats worden die ontwerpen werkelijkheid. Dus zodra een stagiair iets bedacht heeft, vraag ik ze naar beneden te lopen en te praten met de collega die het moet maken. Van die directe feedback leer je veel. Maar het belangrijkste om over te brengen, is dat wat we hier doen onmisbaar is. Nieuwe, duurzame toestellen kunnen alleen in windtunnels gevalideerd worden. Zonder ons werk, gaat er geen vliegtuig de lucht in.”